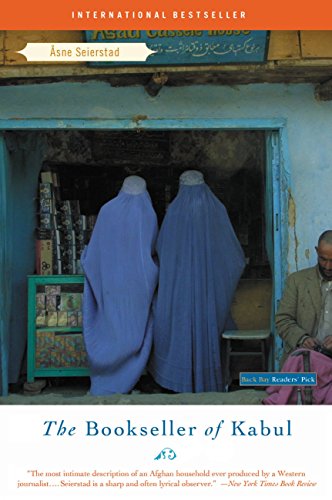

Free The Bookseller Of Kabul Ebooks To Download

This mesmerizing portrait of a proud man who, through three decades and successive repressive regimes, heroically braved persecution to bring books to the people of Kabul has elicited extraordinary praise throughout the world and become a phenomenal international bestseller. The Bookseller of Kabul is startling in its intimacy and its details - a revelation of the plight of Afghan women and a window into the surprising realities of daily life in today's Afghanistan.

File Size: 1494 KB

Print Length: 313 pages

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company (December 1, 2003)

Publication Date: December 1, 2003

Language: English

ASIN: B00XIMUT2G

Text-to-Speech: Enabled

X-Ray: Not Enabled

Word Wise: Enabled

Lending: Not Enabled

Enhanced Typesetting: Enabled

Best Sellers Rank: #92,294 Paid in Kindle Store (See Top 100 Paid in Kindle Store) #17 in Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > History > Asia > India #21 in Books > Biographies & Memoirs > Historical > Asia > India & South Asia #50 in Books > History > Asia > India

Sierstad has written an outstanding book---her writing is lyrical (or at least the translation is!) and the subject is fascinating. Contrary to what other reviewers have said, Sierstad never claims that her family is representative of the Afghani people (in her introduction, she notes that she picked the Khan family because she found them and their stories compelling---she says, however, that the family is by no means typical as they are literate, middle class and urban).That said, the book does provide a penetrating look at a complex and complicated family forced to live under horrific conditions. Within the context of his society, Sultan Khan is an enlightened and liberal man. No fundamentalist, he reads widely and believes in freedom of thought and speech. But for all that Khan is a liberal man in a conservative society---he is still a product of a highly conservative society. As such, he is a polygamist and a man who forces his sons to bind to his will.Khan is not a likeable man but his story, which the author tells in great detail, goes a long way in explaining who he is and why he acts as he does. As a bookseller, Khan was tortured first by the Soviets and then by the Taliban. Not surprisingly, he seeks, above all, to protect himself and all he owns (which for him, includes his family) from the ravages of war. This means, of course, that Khan forces the members of his family to do his bidding (his sons are taken from school and forced to work in his businesses etc.).Khan is a despot. His actions toward his two wives, his children, his siblings and his nephews all reflect his desire to control his fate in a society which has allowed him no control over his own life. That doesn't excuse him, of course.

In November 2001, after the fall of the Taliban, the Norwegian journalist à sne Seierstad befriended a bookseller in Kabul who invited her to his home for dinner. Before long they agreed for her to live in Sultan Khan's home for three months in order to write a book about about his family. The Bookseller of Kabul, an international bestseller translated into thirty languages, and the most successful nonfiction book in Norwegian history, chronicles Seierstad's first person narrative about her experiences of Afghan gender roles, education, politics, religion, and culture. At first Seierstad thought she had met a remarkably liberated Afghan man. Sultan was an ardent bibliophile who loved books and ideas. In a country where three-quarters of the population is illiterate, he had amassed a collection of 10,000 books, including rare manuscripts, that he had squirreled away around town. He survived the Soviet communists and the Islamic fundamentalists, and spent time in jail for anti-Islamic behavior. He despised the Taliban who burned his books. His family was wealthy by local standards, his opinions about women appeared liberal, he bought his wife western clothes in Iran, and derided the burka as a symbol of his beloved country's backwardness and oppression. At home Seierstad discovered an altogether different Sultan, and for the most part her narrative reads like a cultural expose. She begins by telling the story of how Sultan took sixteen-year-old Sonya as his second wife, much to the grief of his first wife Sharifa. At home Sultan was an unapologetic tyrant toward everyone in his family. His two wives and daughters slaved away at cooking and cleaning. He consigned his twelve-year-old son to sell candy in a dark and dank stall that he called "the dreary room.

After having read this book in the original language (Norwegian) as soon as it came out, and then reread it in the English translation, the conclusion remains: this is an intriguing account of an atypical Afghan family's life presented in simplistic and a bit mundane language. The author, Asne Seierstad, is foremost a journalist who has shown a remarkable sense of bravery and an admirable disregard for her snobbish literary critics (she was quickly belittled in her native Norway by fellow writers and critics). Her book, however, is an important contribution to the contemporary literature on Afghan life, culture, women, and even Islam. The strength of the book lies is her observations of the individual family members through her modern feminist Western eyes; however, at times this is also its weakness since it becomes quite obvious that the more "unsympathetic" (male) members of the family do not get quite the nuanced descriptions as the more symphatetic (female) members. The bookseller himself, Sultan Khan, is the most obvious example. Seierstad is not quite able (perhaps understandably so) to portray with conviction his more admirable sides - it is as if his chauvinistic and self-important characteristics cannot coexist with a more complex, idealistic and interesting personality. Sure, she tries to explain that she was grateful to him for his hospitality, and she makes some half-hearted attempts to describe his heroic efforts in his resistance to the Taliban's censorships of his beloved books; however, she is not quite able to convey the bookseller's real and heartfelt motives for doing so. In addition, when referring to his passion for literature (espcially poetry), it seems almost as if it constitutes just a sidenote in Sultan's personality.

Shooting Kabul (The Kabul Chronicles) The Bookseller of Kabul The Vanishing Velázquez: A 19th Century Bookseller's Obsession with a Lost Masterpiece Handwritten Recipes: A Bookseller's Collection of Curious and Wonderful Recipes Forgotten Between the Pages